Why Your Cholesterol Matters Before Symptoms Hit

High cholesterol often shows no signs—until it’s too late. Yet early changes can reset your health trajectory. I’ve seen patients in their 40s, feeling fine, only to discover artery damage already underway. The good news? Small, science-backed shifts now can prevent serious complications later. This isn’t about drastic fixes; it’s about smart, sustainable habits that protect your heart long-term. Think prevention, not reaction.

The Silent Risk: Understanding Pre-Symptomatic High Cholesterol

Cholesterol is essential for life—it helps build cell membranes, produce hormones, and support nerve function. But when levels of certain types of cholesterol become unbalanced, particularly low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), it can silently accumulate in the walls of arteries. This condition, known as dyslipidemia, is one of the leading contributors to cardiovascular disease, the number one cause of death worldwide. What makes it especially dangerous is that it typically causes no symptoms until significant damage has occurred.

Many people assume they would feel something if their cholesterol were too high—fatigue, dizziness, or chest discomfort, perhaps. But in reality, individuals can live for years with dangerously elevated LDL-C and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) without any warning signs. By the time symptoms like angina or shortness of breath appear, plaque buildup in the arteries may already be advanced. Atherosclerosis, the hardening and narrowing of arteries due to cholesterol deposits, progresses gradually and invisibly, often beginning in early adulthood.

Studies show that a substantial portion of the adult population has abnormal lipid levels without knowing it. According to data from national health surveys, more than one in three adults in the United States has high LDL cholesterol, yet only about half are aware of their condition. Even among those who feel healthy and active, routine blood tests frequently reveal lipid imbalances. This underscores a critical point: cholesterol screening cannot wait for symptoms. It must be proactive, not reactive. Regular lipid panel testing, starting as early as age 20 for some individuals, is essential to detect problems before irreversible damage occurs.

The risk is not limited to older adults. Younger women, especially after menopause, face increasing cardiovascular risks due to shifting hormone levels that affect lipid metabolism. Family history, genetics, and lifestyle factors such as diet and physical inactivity further influence an individual’s likelihood of developing dyslipidemia. Because this condition operates beneath the surface, public awareness and routine medical checkups are vital. Early identification allows for timely intervention, which can slow, stop, or even reverse arterial plaque formation.

Why Early Intervention Beats Late Treatment

When it comes to cholesterol management, timing is everything. Research consistently shows that individuals who take steps to improve their lipid profiles early in the course of dyslipidemia experience significantly better long-term outcomes than those who wait until heart disease symptoms emerge. The difference lies not just in extending life expectancy, but in preserving quality of life, avoiding invasive procedures, and reducing the emotional and financial burden of chronic illness.

One of the most compelling reasons to act early is the concept of vascular remodeling. Arteries have a remarkable ability to adapt when cholesterol levels are brought under control. In the early stages of atherosclerosis, plaque is often soft and malleable. With sustained improvements in LDL-C and other risk factors, the body can stabilize these plaques, making them less likely to rupture and cause a heart attack or stroke. Some studies suggest that aggressive lipid-lowering interventions can even lead to modest regression of plaque volume over time.

In contrast, delayed treatment means dealing with more advanced, calcified plaques that are harder to manage and more prone to complications. Once a cardiovascular event occurs—such as a myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke—the focus shifts from prevention to damage control. Recovery can be long, and the risk of future events increases dramatically. Early intervention, on the other hand, keeps the focus on prevention, allowing individuals to maintain independence, vitality, and peace of mind well into later years.

Clinical guidelines from organizations such as the American Heart Association and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force strongly support proactive cholesterol screening and management. These recommendations are based on decades of research showing that lowering LDL-C, even in asymptomatic individuals, reduces the risk of major cardiovascular events. For example, every 40 mg/dL reduction in LDL-C is associated with approximately a 20% lower risk of heart disease over the following decade. This benefit holds true across age groups and risk profiles, reinforcing the value of early action.

From a societal perspective, early cholesterol management also makes economic sense. Preventing heart disease reduces the need for costly interventions like stents, bypass surgery, and long-term medications. It decreases hospitalization rates and improves workforce participation. For families, it means fewer caregiving burdens and less emotional strain. In short, investing in cholesterol control today pays dividends for years to come—not only in personal health but in broader community well-being.

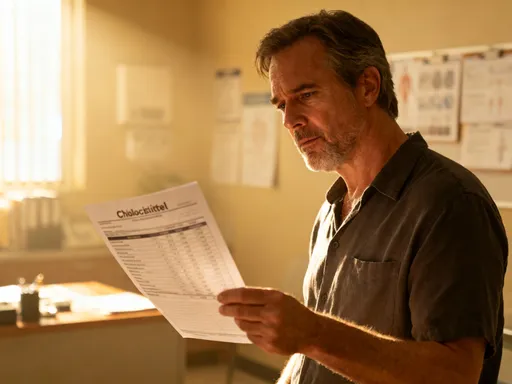

Decoding Your Lipid Panel: Beyond Total Cholesterol

When you get a cholesterol test, the results typically include several key numbers: total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides. While many people focus on the total cholesterol number, this single figure tells only part of the story. A more complete understanding comes from examining each component and how they interact. Knowing what these values mean and how they relate to your personal risk can empower you to make informed decisions about your health.

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is often referred to as “bad” cholesterol because it carries cholesterol particles into the arteries, where they can contribute to plaque formation. However, this label oversimplifies a complex biological process. Not all LDL particles are the same—some are large and buoyant, while others are small and dense. The latter are more likely to penetrate artery walls and trigger inflammation, making them particularly harmful. Advanced testing can measure particle size and number, but even without these tools, keeping LDL-C within target ranges is a crucial goal.

For most healthy adults, an LDL-C level below 100 mg/dL is considered optimal. However, targets become stricter for those with additional risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of early heart disease. In high-risk individuals, doctors may recommend keeping LDL-C below 70 mg/dL. These personalized goals reflect the fact that cholesterol risk must be interpreted in context, not in isolation.

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), often called “good” cholesterol, helps remove excess cholesterol from the bloodstream and transport it to the liver for disposal. While higher HDL-C levels were once thought to be universally protective, recent research suggests the relationship is more nuanced. Very high HDL-C may not always confer extra benefit, and functionality—how well HDL works—may matter more than quantity. Still, maintaining an HDL-C above 50 mg/dL for women is generally considered favorable.

Triglycerides, another type of fat in the blood, also play a role in cardiovascular risk. Elevated levels, especially when combined with low HDL-C and high LDL-C, are linked to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. A normal triglyceride level is below 150 mg/dL, though lower is often better. Non-HDL cholesterol—calculated by subtracting HDL-C from total cholesterol—is increasingly recognized as a powerful predictor of risk because it includes all atherogenic particles, not just LDL.

The real value of a lipid panel lies in pattern recognition. A single number may not tell the full story, but trends over time reveal important insights. For example, a gradual rise in LDL-C or triglycerides, even within “normal” ranges, can signal the need for lifestyle adjustments before levels become problematic. Regular monitoring allows both patients and providers to catch changes early and respond proactively.

Diet That Works: Nutritional Strategies Backed by Science

Nutrition is one of the most powerful tools for managing cholesterol. Unlike quick-fix diets that promise rapid results but are hard to sustain, evidence-based eating patterns focus on long-term health and enjoyment. Three dietary approaches stand out for their proven benefits: the Mediterranean diet, the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, and the Portfolio Diet. Each emphasizes whole foods, fiber, healthy fats, and minimal processed ingredients—principles that align well with the needs of heart health.

The Mediterranean diet, inspired by traditional eating habits in countries like Greece and Italy, is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and fish, with moderate amounts of dairy and poultry and limited red meat and sweets. Numerous studies have shown that this pattern lowers LDL-C, reduces inflammation, and decreases the risk of heart disease. Its emphasis on unsaturated fats, particularly monounsaturated fats from olive oil, helps improve lipid profiles while supporting satiety and flavor.

The DASH diet was originally designed to lower blood pressure, but it also has positive effects on cholesterol. It focuses on reducing sodium intake while increasing potassium, calcium, and magnesium through plant-based foods. By limiting processed and packaged foods—common sources of hidden salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats—DASH naturally supports better lipid control. Combining DASH principles with cholesterol-lowering strategies enhances its cardiovascular benefits.

The Portfolio Diet takes a more targeted approach, incorporating specific foods known to reduce LDL-C. Developed by researchers, this plan includes four key components: soluble fiber (from oats, barley, and legumes), plant sterols (found in fortified foods), nuts (especially almonds and walnuts), and soy protein. Clinical trials have shown that following the Portfolio Diet can lower LDL-C by up to 30%, comparable to the effects of starting a low-dose statin medication.

Individual foods also play a role. Oats and barley contain beta-glucan, a type of soluble fiber that binds to cholesterol in the digestive tract and helps eliminate it. Fatty fish like salmon, mackerel, and sardines provide omega-3 fatty acids, which reduce triglycerides and support heart rhythm stability. Nuts, despite being calorie-dense, improve lipid profiles when consumed in moderation, likely due to their mix of healthy fats, protein, and fiber.

Equally important is what to limit. Trans fats, once common in margarines and packaged snacks, are now largely banned but may still appear in some processed foods as “partially hydrogenated oils.” These fats raise LDL-C and lower HDL-C, making them especially harmful. Refined carbohydrates—such as white bread, pastries, and sugary drinks—can increase triglycerides and contribute to insulin resistance. Replacing these with whole grains, vegetables, and natural sweeteners like fruit can make a meaningful difference.

Practical changes matter more than perfection. Swapping butter for olive oil, choosing steel-cut oats over sugary cereals, adding a handful of nuts to a salad, or grilling fish instead of frying chicken are small steps that add up. Portion control remains important, especially for calorie-rich foods like nuts and oils. The goal is not restriction, but thoughtful, consistent choices that support long-term well-being.

Movement as Medicine: How Physical Activity Influences Lipids

Physical activity is a cornerstone of cholesterol management. Exercise does more than burn calories—it actively improves the way the body processes fats and sugars. Both aerobic and resistance training have been shown to positively influence lipid profiles, making movement a form of medicine with few side effects and many added benefits.

Aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking, cycling, swimming, or dancing, increases heart rate and breathing, improving cardiovascular fitness. Regular aerobic activity raises HDL-C levels, which helps clear cholesterol from the bloodstream. It also enhances insulin sensitivity, reducing the liver’s production of triglycerides. Studies show that engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week can lead to measurable improvements in lipid levels within just a few months.

The mechanisms behind these changes are well understood. During exercise, muscles use more energy, drawing on stored fat and circulating lipids. This increases the activity of enzymes involved in fat metabolism, such as lipoprotein lipase, which helps break down triglyceride-rich particles. Over time, this leads to lower circulating triglycerides and a healthier lipid profile overall.

Resistance training, including weight lifting, bodyweight exercises, or resistance band workouts, also plays a valuable role. While its direct impact on cholesterol may be less pronounced than aerobic exercise, it builds lean muscle mass, which boosts resting metabolic rate. More muscle means the body burns more calories even at rest, helping with weight management—a key factor in lipid control. Combining strength training with aerobic activity provides the most comprehensive benefits.

For women who may have been inactive for years, starting slowly is both safe and effective. A simple routine might begin with 10-minute walks after meals, gradually increasing to 30 minutes most days of the week. Home-based exercises, such as chair squats, wall push-ups, or step-ups, can build strength without requiring equipment. The key is consistency, not intensity. Even modest increases in daily movement—taking the stairs, gardening, or parking farther from store entrances—contribute to better metabolic health.

The American Heart Association recommends a combination of aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities for optimal heart health. Specifically, adults should aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly, along with two or more days of strength training. These guidelines are based on extensive research showing that meeting them reduces the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

Exercise also improves other aspects of health that indirectly support lipid control. It helps regulate blood pressure, reduces stress, improves sleep, and supports healthy body weight. All of these factors work together to create a favorable environment for cardiovascular wellness. For women balancing family and work responsibilities, finding time to move can be challenging, but even short bursts of activity throughout the day can make a difference.

Lifestyle Levers: Sleep, Stress, and Metabolic Health

Cholesterol is not just influenced by diet and exercise—it is deeply connected to overall metabolic health, which includes sleep and stress. Chronic stress and poor sleep patterns can disrupt hormonal balance, leading to elevated cortisol levels, increased inflammation, and unfavorable changes in lipid metabolism. These effects may not be immediate, but over time, they contribute to higher LDL-C and triglycerides, even in individuals who eat well and exercise regularly.

Cortisol, often called the “stress hormone,” plays a vital role in the body’s response to challenges. However, when stress becomes constant—due to work pressures, caregiving responsibilities, or financial concerns—cortisol remains elevated. This can lead to increased fat storage, particularly around the abdomen, and stimulate the liver to produce more cholesterol and triglycerides. Studies have linked chronic stress to higher rates of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease, independent of other risk factors.

Poor sleep has similar consequences. Adults who consistently sleep less than six hours per night are more likely to have elevated LDL-C and triglycerides and lower HDL-C. Sleep deprivation disrupts the balance of hunger-regulating hormones like leptin and ghrelin, leading to increased appetite and cravings for high-fat, high-sugar foods. It also impairs glucose metabolism and increases systemic inflammation, both of which worsen lipid profiles.

The good news is that both stress and sleep can be improved with evidence-based strategies. Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, deep breathing, or gentle yoga, have been shown to reduce cortisol levels and improve emotional regulation. Establishing a consistent daily routine, spending time in nature, and engaging in enjoyable hobbies can also buffer the effects of stress. These are not luxuries—they are essential components of heart health.

Sleep hygiene is equally important. Creating a restful environment—cool, dark, and quiet—supports better sleep quality. Limiting screen time before bed, avoiding caffeine in the afternoon, and maintaining a regular sleep schedule help regulate the body’s internal clock. For women experiencing sleep disturbances related to menopause, such as night sweats or insomnia, discussing options with a healthcare provider can lead to effective solutions without compromising heart health.

Improving sleep and managing stress are not separate from cholesterol control—they are integral to it. A holistic approach that includes nutrition, physical activity, rest, and emotional well-being creates the foundation for lasting cardiovascular resilience. These lifestyle levers work together, each reinforcing the others to produce a greater overall effect.

When Lifestyle Isn’t Enough: The Role of Medical Guidance

While lifestyle changes are powerful, they are not always sufficient to bring cholesterol into a healthy range. Genetics, age, and underlying medical conditions can limit how much improvement is possible through diet and exercise alone. In these cases, medical guidance becomes essential. A healthcare provider can assess overall cardiovascular risk using tools such as the ASCVD (Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease) risk estimator, which considers cholesterol levels, blood pressure, age, gender, race, and smoking status.

Based on this assessment, a doctor may recommend cholesterol-lowering medications, such as statins, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitors. Statins are the most commonly prescribed and have been extensively studied for safety and effectiveness. They work primarily by reducing the liver’s production of cholesterol and increasing the removal of LDL-C from the blood. For many individuals, especially those at high risk, the benefits of statins far outweigh the potential side effects.

It is important to understand that taking medication does not replace the need for healthy habits. Even when on pharmacologic therapy, diet, exercise, sleep, and stress management remain foundational. Medications enhance the effects of lifestyle changes; they do not substitute for them. The most successful outcomes occur when both approaches are used together.

Some people hesitate to start medication due to concerns about side effects or a desire to “do it naturally.” While these feelings are understandable, it is crucial to base decisions on accurate information. For most patients, statins are well tolerated, and serious side effects are rare. The decision to use medication should be made in partnership with a healthcare provider, based on individual risk and goals.

Regular follow-up and monitoring are also key. Lipid panels should be repeated periodically to assess progress and adjust treatment as needed. Open communication with a doctor ensures that any concerns are addressed and that the chosen approach supports long-term health and peace of mind.

Conclusion

Preventing cardiovascular disease starts long before symptoms appear. Managing cholesterol early through informed, consistent choices empowers lasting health. This proactive mindset transforms how we view wellness—not as a reaction to illness, but as a daily commitment to resilience. Small, sustainable changes in diet, movement, sleep, and stress management can have a profound impact over time. When necessary, medical guidance provides additional support, ensuring that risk is minimized and health is preserved. By taking action today, women can protect their hearts, maintain independence, and enjoy a vibrant future. The power to change your health trajectory is within reach—one thoughtful choice at a time.